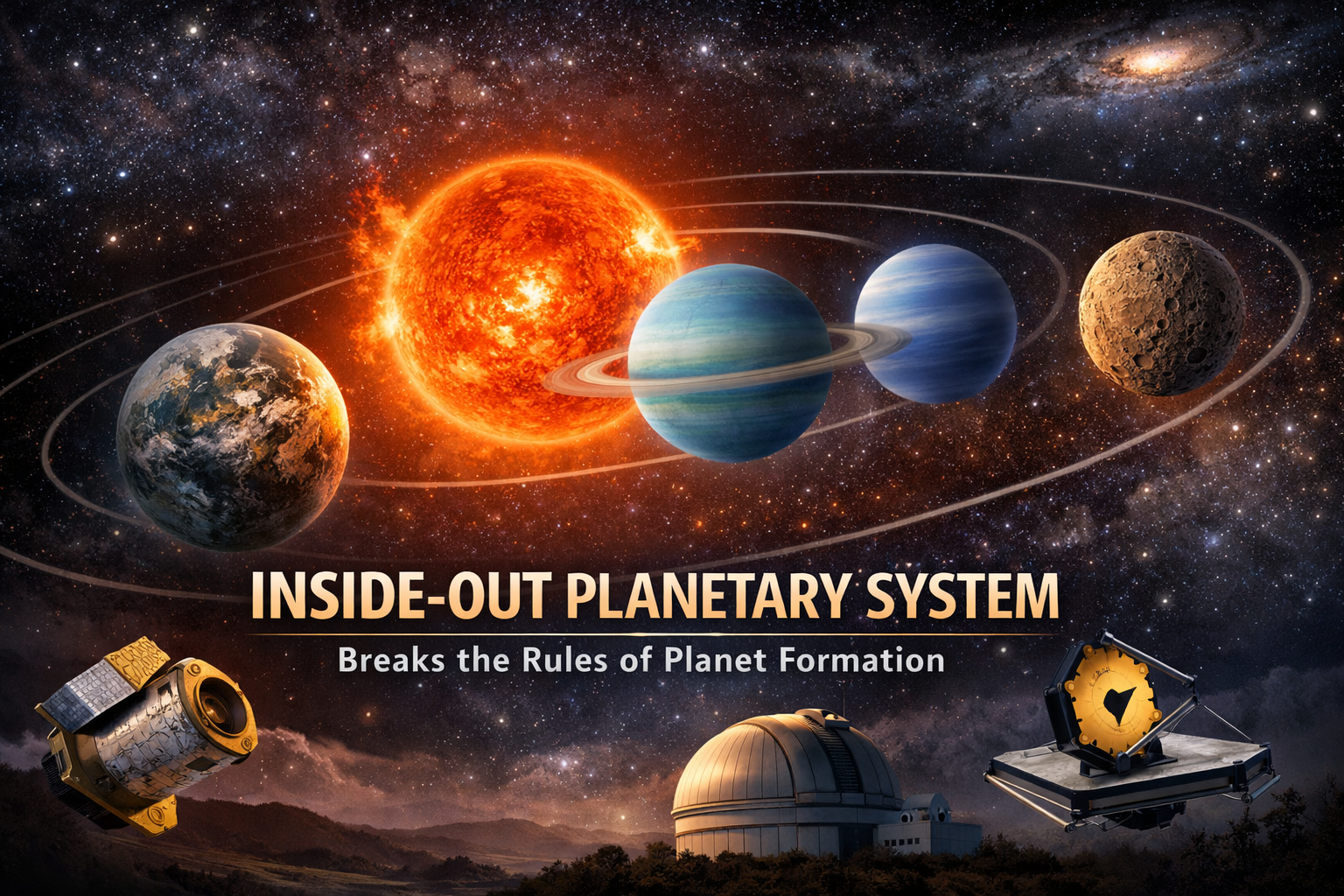

Astronomers discover a rocky world where a gas giant should be, forcing scientists to reconsider fundamental theories

February 15, 2026

An international team of astronomers has discovered a planetary system 116 light-years from Earth that breaks one of the most fundamental rules of planet formation, potentially upending decades of established scientific understanding about how solar systems take shape.

The system orbiting the red dwarf star LHS 1903 in the constellation Lynx displays what researchers are calling an “inside-out” arrangement that contradicts patterns observed across the Milky Way and in our own Solar System. Published in the journal Science on February 12, the discovery centers on a fourth planet that shouldn’t exist where it does.

An Unexpected Arrangement

Using the European Space Agency’s CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite (CHEOPS), along with ground-based telescopes, researchers identified four planets orbiting LHS 1903. The first three followed expectations: LHS 1903 b, a rocky planet close to the star, followed by two gaseous worlds, LHS 1903 c and LHS 1903 d, similar to smaller versions of Neptune.

But the fourth planet told a different story. LHS 1903 e, orbiting farthest from its host star with a period of 29.3 days, appeared to be rocky rather than gaseous. This creates an unprecedented planetary sequence: rocky, gaseous, gaseous, rocky.

“This strange disorder makes it a unique inside-out system,” said lead author Thomas Wilson from the University of Warwick. “Rocky planets don’t usually form far away from their home star, on the outside of the gaseous worlds.”

Breaking the Pattern

For decades, astronomers have observed a consistent pattern in planetary systems. In our own Solar System, the inner planets—Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars—are rocky, while the outer planets—Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune—are gaseous. This arrangement has been seen across hundreds of planetary systems throughout the galaxy.

The pattern emerges from the physics of planet formation. Close to a star, intense radiation sweeps away lightweight gases, leaving behind only dense, solid cores that become rocky planets. Farther out, where temperatures are cooler, gas can accumulate around rocky cores, creating gas giants.

LHS 1903 violates this fundamental principle. Its outermost planet appears to be a naked rocky core with no gaseous envelope.

A Late Bloomer from Another Era

The research team considered several explanations for the anomaly. Could the planets have swapped positions through gravitational interactions? Might the outer planet have lost its atmosphere in a catastrophic collision? Both scenarios were ruled out through detailed analysis.

Instead, the evidence points toward what researchers call “gas-depleted formation”—a process in which the outermost planet formed much later than its siblings, long after the protoplanetary disk had lost most of its gas.

“We use transit photometry and radial velocity measurements to detect and characterize four exoplanets,” the researchers wrote in their Science paper. The derived densities indicate the most distant planet from the host star has no gaseous envelope, suggesting it formed from gas-depleted material.

The hypothesis suggests the planets formed sequentially, one after another, beginning with the innermost worlds. By the time conditions allowed the fourth planet to coalesce, the gas that would normally create a thick atmosphere had already dissipated.

Implications for Planetary Science

The discovery has significant implications for understanding the “radius valley”—an observed gap in the size distribution of exoplanets that separates smaller rocky worlds from larger gaseous ones. Scientists have debated whether this gap results from planets losing their atmospheres over time or from never forming atmospheres in the first place.

“Confirming the uniqueness of this remarkable system using my specialized analysis pipeline was incredibly exciting,” said co-author Ancy Anna John from the University of Birmingham. “It truly felt like standing at the forefront of scientific discovery.”

Sara Seager, professor of planetary science and physics at MIT and a study co-author, suggested the finding may offer “some of the first evidence for flipping the script on how planets form around the most common stars in our galaxy.” However, she cautioned that the interpretation remains challenging and debate continues.

Questions and Future Research

Not all experts are fully convinced by the gas-depleted formation hypothesis. Lauren Weiss, an astrophysicist at the University of Notre Dame who was not involved in the study, praised the quality of the research but noted she would have liked to see more exploration of alternative scenarios, particularly the possibility of a giant impact stripping away the planet’s atmosphere.

Wilson and his colleagues acknowledge uncertainties remain. They plan to use the James Webb Space Telescope to study the atmospheres of the LHS 1903 planets in greater detail, which could provide crucial evidence about how they formed.

“Even in a maturing field, new discoveries can remind us that we still have a long way to go in understanding how planetary systems are built,” Seager noted.

A Common Star with Uncommon Planets

LHS 1903 is a red dwarf, the most common type of star in the universe. These small, cool stars are dimmer than our Sun and have become prime targets in the search for exoplanets. The star resides in the Milky Way’s thick disk, an older stellar population, located in the Luyten Half-Second catalogue—a list of stars with significant proper motion first compiled in 1979.

The discovery raises fundamental questions about planetary diversity. Isabel Rebollido, a planetary disc researcher at ESA, explained that planet formation theories have historically been based on what we observe in our own Solar System. “They force us to question our understanding and make us reconsider established theories of planet formation,” she said.

The finding also prompts a deeper question about our cosmic neighborhood: “They make us wonder how special the order of the planets is that we teach our children, and if maybe it is our home Solar System that is the weird one after all.”

As astronomers continue discovering more planetary systems among the more than 6,000 known exoplanets, LHS 1903 serves as a reminder that the universe still holds surprises that challenge our most fundamental assumptions about how worlds are born.